Posts tagged ‘Tucson’

Radical bland: unfolding the New Topographics

My first encounter with the New Topographics did not go well. I was 20, and in college, and stumbled into the Robert Adams show at the Yale University Museum of Art in 2002 when I was there to attend a lecture.

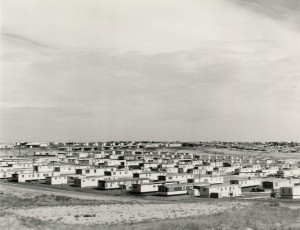

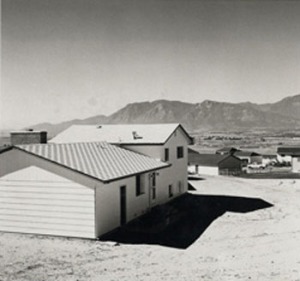

I wandered up and down the walls of what seemed like endless, terrifyingly boring black and white images of ugly houses, cul-de-sacs, clear-cutting, and mines. I could not figure out what these pictures were really about, or why anyone would want to look at them. When I looked at them, I just felt depressed.

Ah HA, I now want to say. Hey, Eliza, that WAS the point! That’s what makes them so interesting and disarming and beautiful. We are building a boring world for ourselves. Which, when you realize it, is searingly painful to witness and be a part of. Eliza, Eliza, wake up!

But Eliza, junior-in-college, is utterly impervious to my shouts. It was not until a few years later, when I found myself in Arizona, a whole new part of the American West than I had previously experienced, that I began to really feel what those pictures are talking about.

It helped that I met and studied with Bill Jenkins, the curator responsible for the New Topographics exhibition in 1975, and Mark Klett, one of the foremost landscape photographers working in the U.S. Their personal experiences and their view of life in the Sonoran Desert, fast disappearing beneath box stores and condo complexes, reshaped my connection to landscape photography, particularly photographs of the western U.S.

And now, when I think about the New Topographics, I think about that group of artists as some of the most serious, purposeful social change photographers that I know about.

One of the things that interests me about them is that they use images in a different way than I might have expected. They use images to create social change by helping their viewers understand what society is, in the first place. They aren’t showing just what’s wrong with it, or what it would look like if things were better—they are showing me what my own culture is. They are telling me stories about myself.

I love that! To me, that is so often what makes a great work of art—the ability of the artist to articulate how I feel, or how life feels, in a way that I’ve never been able to.

And social change is such an ambiguous phrase, and such a nuanced and many-layered process—what a great idea it is to start change by understanding where you are (in space, in time, in community-building) in the first place.

A new show reproducing the original selection of artists, with a few additions, opens this week at the Center for Creative Photography in Tucson, Arizona, with an artist’s talk at the opening reception, given by Bill Jenkins, Joe Deal and Frank Gohlke. There is also a catalogue available, which I just bought. Details below, taken from the CCP website.

New Topographics, February 19 – May 16, 2010

The exhibition New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-altered Landscape, held in 1975 at George Eastman House, signaled the emergence of a new approach to landscape photography. A new version of this seminal exhibition re-examines more than 100 works from the 1975 show, as well as some 30 prints and books by other relevant artists to provide additional historical and contemporary context. This reconsideration demonstrates both the historical significance of these pictures and their continued relevance today.

Opening Reception and Artists’ Talk, Friday, February 19, Reception at 5 p.m., Discussion at 6 p.m.

Join Bill Jenkins, the curator of the original 1975 presentation of New Topographics and exhibiting artists Joe Deal and Frank Gohlke as they discuss the origins and impact of that seminal project. Moderated by Britt Salvesen, Department Head and Curator of the Wallis Annenberg Department of Photography, and the Department Head and Curator of Prints and Drawings at the Los Angeles County Museum of Art.

Josh Schachter, Tucson’s superhero of community-based art

“To me, great images that are going to create change have a sense of emotion and question our most basic assumptions about the world.”

This is Josh Schachter talking; a community-based artist living in Tucson, Arizona.

Community-based photography, which gained international attention thanks to Zana Briski and the 2004 Academy-Award-winning documentary film Born into Brothels, is when artists lead a community through a process of making and exhibiting art.

“When I was doing my graduate work in Forestry and Environmental Management, I wasn’t that focused on photography,” says Schachter. “And I guess as I started doing urban forestry in New Haven, I realized I didn’t really know what was going on in my own city…

“And so I started really wanting to find out how community members perceived their own community and their own environment, vs. how I would tell the story of their neighborhoods and their communities if I was hired as a documentary photographer.”

So four years ago Schachter began to build the Finding Voice Project, which merges a photography curriculum with a more traditional after-school ESL program for refugee and immigrant teenagers.

Instead of advocating for his students by documenting them directly, Schacter teaches his students how to advocate for themselves, first by creating a story and then by distributing that story to the relevant audiences.

“Great images, that aren’t effectively distributed, don’t create a lot of social change,” he says.

But there are some meaty ethical conundrums inherent in this kind of work. One is how to achieve the appropriate balance between your voice as the artist, and the voices of the community you’re working with. “My own aesthetic preferences do come through in their work. Whether I want them to or not,” says Schachter of his students. “So I think it really has to be seen as a collaboration.”

Another issue is the sustainability of each project. Are the skills you are teaching relevant to that community? Will the opportunities you create in a place continue after you leave? “Another big challenge is thinking about how to match the technology with the community’s needs and capacity. So I also often question whether digital photography is the right tool, in a community with no power?!”

Josh laughs as he says that, because it seems so obviously silly. But of course, workshops in rural areas—off the grid—use digital media all the time, and the reasons for it are complex. Sometimes there are generators. Used digital cameras are cheap, abundant, and what donors and workshop facilitators are familiar with. And it’s not that it’s wrong to use them…it’s just that it isn’t automatically right.

“Sometimes people say that most of photography is just being there,” says Schachter. “And I think if you’ve lived you’re whole life in a place, you know where to be. And I think that in itself influences the nature of the images that the communities produce.”

All of the previous images have been made by Josh’s students. Below is one of his own.

And a quick shout out: Andy Levin of 100Eyes is leading a community based workshop in Haiti and needs cameras. It was scheduled prior to the earthquake, and they are proceeding as planned. If you have any cameras you could donate, please email him: levin.pix AT gmail.com