The key? Intimacy.

March 3, 2010 at 5:30 am Leave a comment

Kathleen Hennessy is the Director of Photography at the San Francisco Chronicle and has just joined PhotoPhilanthropy as the Activist Award Director for 2010.

I asked her everything that came rushing into my head. What is your editing process like? And how do you think photography creates social change? And what advice do you have for people submitting photo essays to PhotoPhilanthropy?

Here’s what she said:

Some of the essays I looked at from last year’s submissions were not as strong as they could be because they don’t really have a focus. What I’m seeing is that people are photographing things that are happening around them, but I don’t know what the story is. I don’t know what they’re trying to say.

If you were going to document a pediatric surgical team, for example, it would be really great to have some theme that you follow—maybe a doctor, or a patient—so that you connect with somebody.

I think it’s really important to establish that connection with another individual. Because if you don’t, if the viewer doesn’t get to connect with any person in a deeper way, then everybody becomes sort of anonymous. And that’s a problem. I think you get a much more emotional reaction when you really feel like you got to know someone and their story. And then that one story illustrates the larger organization and the larger issue.

When I was working with Deanne Fitzmaurice on the Pulitzer prize winning story, she got very close to the subject.

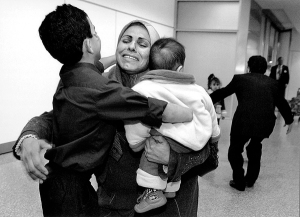

It was as story about an Iraqi boy named Saleh, who picked up a bomb he thought was ball. It exploded, killing his brother and severely injuring him. He was eventually brought to Oakland, California for treatment. She worked on that story for about a year and got close to the family. It was impossible not to.

And even though she didn’t want to, she had to show the moments where he was acting up or getting frustrated because that was the whole story. She had to stay somewhat detached. Because the goal of photojournalism is to have the credibility that you are telling the truth.

An artist, on the other hand, is seeking their own truth, in my opinion.

So when you are doing this kind of collaborative work with an organization, you really have to believe in what that organization is doing. If you go in there and you think, “Wow, what are they doing?” then maybe you shouldn’t do it.

It’s also important to really do your homework. You should talk to people who run the organization, who are in the field, and ask them what they see every day. And sometimes you have to be a filter, because they may tell you what they think is a great story, and it may not be. For example, it may not be visual. It has to be a visual story. And it has to prompt an emotional reaction that connects the viewer to the subject

The best thing to do is observe. Spend some time before you ever pick up the camera, observing what they do. You need to think about what it is that attracted you to the story. What is the story that you want to tell?

And take notes. I always say to photographers—who are not necessarily writers—take notes. Jot down words that represent what you are feeling, and then think about how to capture that feeling.

You asked about creating social change as an editor. Well, we were having a staff meeting, and talking about ideas. I wanted to do some stories related to the economy, because that is one of the big issues of the year.

So Brant Ward, one of our staff photographers at the Chronicle, said, “I really want to do something in Chinatown. It’s very difficult to get access to stories there, and there is a lot going on.”

He’s been at the Chronicle for 25 years. He found his own contact and she connected him with the Mo family, who live in a one room flat. The room has no private bathroom or kitchen so they share with the other families living in the building, which is called an SRO: single room occupancy.

He worked through a community activist who spoke the language and was trusted by the community. I think that’s a very important connection, so that when you are introduced to the community, you are also trusted.

The father, Zhihua, a carpenter and plumber, was out of work. The mom, Lifen, was making minimum wage handing out restaurant coupons to tourists. The grandfather, who lived a block away in another SRO, had a nurse taking care of him but when Zhihua lost his job they could no longer afford the nurse and Zhihua starting taken care of his dad daily.

The grandfather couldn’t walk, and his son told Brant, “When I take him to the doctor, I have to put him on my back and carry him up two flights of stairs.” And so Brant knew that was the picture he needed to get. And so he kept waiting and waiting for that day to come, and it finally did.

When the story was published, it was on the front page with two inside pages full of photographs. There was a real out-pouring of support. Brant received many emails from people who wanted to help, both monetarily and with job offers. Zihua is now working again.

So you hope that you have an impact, and it can be something small like one person getting a job. Or it could be a larger impact, like with Deanne’s story. After her story was published, Saleh’s family received thousands and thousands of dollars in donations and his mother and sisters were granted asylum in the U.S.

And that’s the beauty of documentary photography: hopefully your goal is to have some sort of impact.

Brant told the story of Chinatown through one family. Which gets back to what I was saying in the beginning. You’re more connected through one family than if it was a series of pictures of multiple families who lived in single rooms. I feel more connected to that issue because I know what this one family’s life is like.

If you stay with one story, if you stay with one focus, there’s more intimacy there. And to me that is the key to a successful story or a successful photo essay, intimacy.

And a lot of times you may see a collection of photographs, and they may be beautiful, but I’m left wondering what are they trying to say. Other than, here’s a nonprofit, or here’s a lot of suffering people.

I loved Dmitry Markov‘s story, which won the amateur award, because it was so focused. One group of kids, one place—I really got a sense of what their lives were like. Beautiful intimacy with the shaving of the head, wonderful use of light. I felt a sense of connection with the community there because I could see how the boys reacted to each other. I thought that was really successful.

Entry filed under: About PhotoPhilanthropy, Social Change Photography, Uncategorized. Tags: a visual story, activist award, advice, Brant Ward, california, Chinatown, collaboration, connection, Deanne Fitzmaurice, editing, emotion, Iraq, journalism, Kathleen Hennessy, media, narrative, news, newspaper, nonprofit, photo editor, photography, photojournalism, pictures, Pulitzer, questions, Saleh, San Francisco Chronicle, SF Gate, social change, SRO's, staff photographers, stories.

PhotoPhilanthropy in the field: observations from Haiti PhotoPhilanthropy in the Field: notes from King’s Hospital, Haiti

Trackback this post | Subscribe to the comments via RSS Feed